The future of healthcare will not be decided by a single breakthrough. It will be decided by who gets to deploy the breakthrough and who gets left behind.

The World Health Organization says digital health innovation is advancing at an “unprecedented scale,” and the World Economic Forum highlights how AI, gene editing, and other medical technologies are pushing detection and treatment forward. But the distribution problem persists: tech can widen gaps if infrastructure, trust, governance, and financing lag behind.

Patient access remains uneven. Millions still lack timely primary care, essential medicines, diagnostic capacity, and safe surgical services. Meanwhile, political volatility, workforce strain, and fragmented data systems are slowing down the adoption of even proven interventions.

Physicians are watching four potential “pace-setters” compete and collide: national governments, private companies and tech firms, international agencies, and physician-led initiatives. Sermo community’s survey data makes one thing clear: clinicians don’t expect a single hero to transform the healthcare industry. They expect a coalition, with the physicians’ role to push it toward equity and clinical reality.

What sector will lead healthcare innovation moving forward?

Sermo recently surveyed over 1,500 physicians to discover who they believe is most likely to lead healthcare innovation.

National governments

Physicians gave national governments17% of the vote as the best-positioned leaders. That number reads like guarded realism: governments are essential for universal coverage, regulation, and public health infrastructure, but often too slow to keep pace with clinical innovation cycles.

That tension shows up in the broader industry forecast. Deloitte’s 2025 global health care executive survey emphasizes that leaders are prioritizing efficiency and productivity while investing in digital platforms, but it also highlights the friction caused by policy complexity and the need to navigate diverse regulatory environments. In other words, even when funding is available, execution can stall at the implementation stage, ultimately limiting patient outcomes and access.

Physicians see governments as the only actors who can credibly guarantee equity at scale, but not necessarily the ones who will move first.

To connect the equity argument directly to frontline care, one physician in Spain points to the governance advantage of public stewardship on Sermo. The physician comments, “Leadership in health should come from the public sector, which is the only sector that can guarantee equity and universal access. Technology can support this, but always in the service of sound public policies and social well-being, not economic profit.”

Private companies or tech firms

37% of surveyed physicians chose private companies as the sector leading medical transformation, the top-voted option. Physicians aren’t naïve about the profit motive. They’re pragmatic about execution speed, capital, and the ability to build at scale to impact patient care.

EY’s health trends for 2026 point to why the private sector’s pace is hard to match. Mostly because healthcare is moving toward a “new value equation,” more patient-enabled care, and tech-driven transformation that demands investment and iteration. Deloitte similarly reports broad investment momentum in digital tools and platforms as a core strategy. But the obstacle is legitimacy. “Innovation” can become synonymous with monetization unless incentives are constrained by outcomes, safety, and access.

That ambivalence is bluntly captured by one U.S. pathologist, who shares on Sermo, “Private firms, with a strong profit motive, will lead innovations.”

And it’s reinforced by global workforce and delivery realities. Bernard Marr’s 2026 tech trends include virtual hospitals and AI agents that reshape the patient journey, but these models still require governance, privacy protections, and equitable access to broadband and devices.

International organizations (e.g., WHO)

In the Sermo survey, International organizations received 18% of the vote, representing not dismissal, but rather skepticism about agility and enforcement power in an increasingly politically fractured world.

The WHO’s best role is not to “innovate like a startup,” but to set standards, coordinate cross-border response, and push interoperability and ethics frameworks that prevent digital health transformation from becoming a patchwork of incompatible systems. The World Economic Forum’s framing is consistent. Healthcare innovation is accelerating, but it needs coordination across sectors to translate breakthroughs into widespread patient benefit.

The Sermo community also voiced concern that international organizations can struggle to lead when legitimacy and political alignment are contested. International coordination is necessary, but insufficient without capital and national enforcement.

One physician in Spain puts it plainly, “It’s incomprehensible at this time that international organizations can lead healthcare; moreover, that’s no longer possible. Agility in innovation and, essentially, capital are only possible from large companies, but they run the risk of the opposite: innovation for enrichment, which leads to the exclusion of economically uninteresting communities. For this partnership to work, it would require, in addition to international organizations and large capital, clear government regulation and initiatives from physicians free from conflicts of interest.”

Physician-led initiatives

Physician-led initiatives garnered 27% of the vote in the Sermo survey, which is significant because it reflects a belief in clinical governance, not just clinical labor. Physicians see themselves as the corrective force that can keep medical innovation aligned with non-biased outcomes, safety, and equity.

This is consistent with broader evidence that physicians increasingly view leadership and identity formation as part of modern practice, not an optional extra. Harvard’s discussion of physicians at the forefront of healthcare technology innovation emphasizes that clinicians play a critical role in shaping effective adoption because they understand workflow, patient risk, and real-world constraints.

Physicians also recognize the risk of concentrating power. As one physician discusses on Sermo, “Physicians should lead health policies and have a significant weight in advising governments at a national level, but they should not have control in fund allocation. Weights and balances are needed to prevent corruption.”

And when it comes to depoliticizing care delivery, clinicians are calling for a bigger role in protecting the evidence base as one OBGYN shares, “Physicians are going to have to get involved in the non-politicization of health care around the world.”

One additional nuance from the Sermo thread is that “leadership” may not be a single entity at all, but a structured partnership:

“As a physician, I believe no single entity will lead healthcare. True innovation will come from a collective model. This includes clinicians engaging with patients on preventative care, researchers converting discoveries into treatments, and policymakers ensuring equitable access. The future leader will be this partnership itself, focused on keeping populations healthy, not just treating disease,” says a GP from Spain.

Innovations in healthcare: Countries leading the charge

In the Sermo survey, we asked which country our physician members believe will emerge as the strongest driver of healthcare innovation in the next decade:

United States (39%)

The U.S. led the votes at 39%. The logic is based on historic trends: deep biotech pipelines, strong venture funding, and rapid commercialization. But physicians are also watching internal instability and trust erosion as potential drags on leadership. Between February 2020 and June 2022, public confidence significantly dropped in the NIH (-25%), DHHS (-13%), state health departments (-16%), and professional medical organizations (-26%). Despite a slight rebound by October 2024, trust in all of these key public health institutions remains well below February 2020 levels.

Political turmoil has also slumped healthcare innovation in the U.S. Trump called for a nearly 40% reduction in NIH funding, among cuts across CDC and large non-HHS science agencies. Fortunately, Congress’s FY2026 funding direction has mostly held research spending near prior levels (and bumped NIH slightly), signaling bipartisan resistance to large-scale federal research retrenchment—even as policy/administrative changes can still affect how many grants are awarded and which research areas proceed.

China (26%)

China captured 26% of physicians’ votes and is seen as a rapidly scaling technology power. The opportunity is speed and manufacturing capacity. The risks include geopolitical tensions and the possibility that strategic priorities distort health outcomes.

A 2025 review in PubMed describes how centralized data, policy incentives, and commercialization dynamics have supported a globally competitive AI medical ecosystem in China, led by a top-down, “whole-of-society” approach. A 2025 review in the publication Nature describes China’s transformation from a generics-dominated market toward a major player in innovative drug development, including regulatory modernization and clinical trial advances.

China is rapidly transforming, but as an OBGYN from the USA explains, “China will be a big driver – but the political arena may drive innovation astray.”

However, there are risks. The global pharmaceutical supply chain, particularly regarding APIs (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients) and KSMs (Key Starting Materials), faces increasing geopolitical risk.

- Supply Chain as a Geopolitical Lever: Concerns are rising that supply chain dominance could be “weaponized” in geopolitical conflicts, as highlighted in a 2025 U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission chapter. This leverage poses a significant risk.

- Pharmaceuticals as a Tool in Trade Conflict: Analysis from the Atlantic Council frames pharmaceuticals as a potential leverage point in trade disputes, outlining the strategic logic and inherent dangers of this approach.

- Tension in Global Collaboration: Despite growing geopolitical and trade constraints, extensive collaboration continues, with China playing a substantial role in global drug development (as reported by Reuters, citing Pfizer’s CEO). This creates a tension between the need for speed and scale in development and the headwinds from geopolitical pressures, especially in the face of Trump’s recent tariffs against China.

The healthcare innovation ‘arms race’ is well summarized by an OBGYN on Sermo who warns, “With the US abdicating leadership in science and technology, it is only a matter of time before China leads globally in technology and influence.”

European Union nations collectively (24%)

24% of physicians chose the EU bloc as the upcoming healthcare innovation leader. Physicians often associate Europe with stronger privacy norms, broader coverage structures, and a collaborative baseline that can support equitable deployment.

The European Union is increasingly framed as an emerging healthcare‑innovation leader, with Horizon Europe and the European Health Union explicitly positioning the bloc as a hub for coordinated, cross‑border life sciences and digital‑health R&D. GDPR‑aligned frameworks and the European Health Data Space showcase privacy as a priority, embedding patient data protection and ethics into health technology deployment and adoption. At the same time, most EU countries operate under universal‑coverage or heavily regulated insurance models, which clinicians frequently link to broader coverage structures and lower financial barriers to care.

A rheumatologist from the USA summarizes, “Countries with national healthcare are best positioned to offer insights on global healthcare innovation due in part to the presence of a collaborative mindset already. Availability of funds and barriers of regulatory agencies will decide the rapidity of progress.”

United Kingdom (4%)

The UK received just 4% of the vote, but it remains influential as a testbed for national-scale deployment models. For example, the NHS has publicly discussed virtual hospital directions, reflecting how centralized systems can pilot access models at scale.

The UK’s relatively lower ranking may also reflect post-Brexit regulatory divergence, which could complicate multinational partnerships and market access compared to the unified European Health Data Space. Despite this, the National Health Service (NHS) continues to offer a unique, single-payer environment for large-scale, real-world data studies and population health pilots, keeping it relevant to global innovation research.

Saudi Arabia (2%)

Saudi Arabia consistently appears in “outsized pilot” conversations because of rapid investment in national digital infrastructure. One concrete example often cited is Saudi Arabia’s SEHA Virtual Hospital, which connects 130 healthcare facilities and is described as having the capacity to treat 400,000 patients per year.

The country’s Vision 2030 aims to fundamentally transform its healthcare system through privatization and digital integration, making it a key regional player. This aggressive, top-down investment strategy creates a unique environment for rapid piloting and deployment of cutting-edge health technologies.

Switzerland (3%)

3% of physicians chose Switzerland as the upcoming healthcare innovation leader. This reflects its role as a biotech and pharma hub with deep scientific capacity and cross-border health innovation influence, even if it isn’t always the loudest “platform” economy.

Switzerland combines a highly regulated, universal‑coverage Bismarck‑style system with a dense ecosystem of medtech, biotech, and digital‑health startups supported by strong research institutions and innovation‑focused funding programs. The country’s innovation profile is further amplified by major events such as the Health Tech Summit and Personalized Health conferences, which position Switzerland as a hub for AI‑driven decision support, personalized medicine, and next‑generation therapeutic development. Finally, a reality check comes from a pediatrician in Mexico, who explains on Sermo, “Medicine has advanced considerably in recent times, and there are countries that are leading the way in advancing these advances. It is unlikely that a guide can be defined, since some countries are more advanced in some aspects than others. Therefore, we must wait and see how things progress over time.”

Healthcare technologies with the biggest global impact

Physicians are not betting on a single device or app, but on categories that change cost curves, workforce capacity, and diagnostic reach.

AI and digital health (62%)

AI and digital health dominated Sermo’s survey, with 62% of physicians choosing it as the healthcare tech with the biggest global impact. This aligns with global trend reporting that highlights AI agents, AI-driven diagnosis, and virtual hospital models as major accelerators for access and efficiency. AI for better patient outcomes is already used in diagnostics, patient monitoring, and treatment planning, but concerns persist about accuracy, overreliance, ethics, and patient impact.

The role of global policy in the adoption of artificial intelligence is critical. Countries with clear regulatory pathways, strong privacy rules, and interoperable infrastructure will deploy AI faster and more safely. Without these guardrails, AI becomes a pilot program that never scales.

A physician in Turkey connects artificial intelligence’s value to what clinicians want most: reclaimed time and influence by assisting with scheduling, patient data entry, billing, and claims.

A family medicine physician shares on Sermo, “I think AI will free up doctors’ time, enabling them to take a more active role in shaping policies, driving innovation, and giving greater attention to their patients.”

And the same thread acknowledges who is likely to build it first, for better and worse:

“Without a doubt, the development of AI in healthcare will be the great revolution in medicine in the coming years, and private companies and foundations will play a leading role in this, possibly in collaboration with and/or subrogation of government entities.”

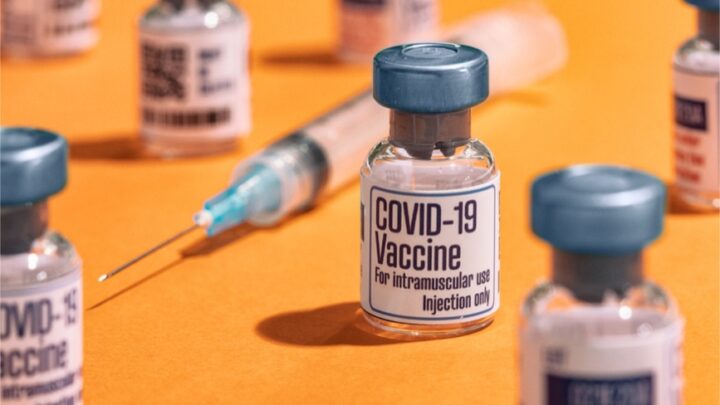

New drug/therapy development (18%)

18% of surveyed physicians chose new drug and therapy development as the healthcare innovation with the biggest global impact. This includes genomics, vaccine platforms, and advanced biologics.

Leading healthcare industry breakthroughs include long‑acting HIV‑prevention agents such as lenacapavir (Yeztugo) for curbing new infections. In oncology and immunology, first‑in‑class bispecific antibodies and CAR‑T therapies (e.g., linvoseltamab and Breyanzi) are expanding options for heavily pretreated multiple myeloma and rare lymphomas, while novel oral antibiotics like gepotidacin and targeted biologics such as voyxact for IgA nephropathy are addressing long‑standing therapeutic gaps in infection and kidney disease.

Emerging treatment modalities such as mRNA‑based cancer vaccines (e.g., mRNA‑4157 combined with pembrolizumab) and AI‑driven discovery platforms are accelerating the pipeline of precision oncology and rare‑disease therapies, with 2025 alone bringing over 40 novel FDA approvals that span durable formulations, non‑opioid pain therapies, and first‑ever treatments for conditions like Barth syndrome and diffuse midline glioma. Looking ahead, 2026 is expected to feature high‑impact launches such as orexin‑2 agonists for narcolepsy, dual GLP‑1/amylin obesity agents like CagriSema, and pan‑respiratory mRNA vaccines, reinforcing a shift toward chronic‑disease modification, personalized immunotherapies, and AI‑integrated drug development at a global scale.

One hematologist connects the dots between computational acceleration and next-gen therapeutics on Sermo, explaining, “AI and ML will undoubtedly help with drug repurposing, but CRISPR therapy will be a game-changer for the treatment of diseases.”

Public health policy and prevention (12%)

Public health policy and prevention came in at 12%. Healthcare prevention is the highest-leverage innovation, but it’s the hardest to fund, measure, and politically sustain. Consistent public health policy and prevention require sustained political will and a commitment to long-term medical funding, both of which are notoriously difficult to secure in volatile political and economic climates.

This is where healthcare innovation shifts from wearable medical devices, clinical software, and new technologies to credible governance, trust-building, and community-delivery systems.

Universal healthcare financing models (9%)

Universal healthcare financing models accounted for 9%, but financing is the substrate beneath every other medical innovation. Universal healthcare financing models—such as single‑payer, national health insurance, and regulated multi‑payer systems—are increasingly treated as “health‑tech platforms” because they create the payment and data infrastructure needed to scale digital tools, AI, and value‑based care globally.

These healthcare models can standardize reimbursement, reduce billing fragmentation, and support interoperable electronic patient records, enabling large‑scale deployment of telemedicine, predictive data analytics, and population‑health platforms that would otherwise be siloed across insurers and regions.

Without sustainable payment models, the “best” medical technology innovations become boutique medicine, far from the reach of the average hospital or patient. Physicians see financing reform as slow, political, and country-specific. But when it changes, it accelerates development across the entire healthcare system.

Political and systemic barriers to progress in healthcare

We asked physicians on Sermo what the biggest barrier to global healthcare progress is, and this is how they responded:

- 40% – Political instability

- 32% – Lack of funding

- 17% – Regulatory hurdles

- 11% – Physician workforce shortages

Non-technological obstacles are the real bottleneck to healthcare system innovation. Research on digital health equity consistently points to structural barriers, such as governance gaps, fragmented implementation capacity, and unequal access to enabling infrastructure.

Political instability (40%)

Political instability disrupts supply chains, undermines trust, and turns health policy into a pendulum. It also directly shapes whether AI in medicine is adopted responsibly. Where governance is weak, patient data protections erode, procurement becomes politicized, and tools get deployed without adequate clinical or physician oversight.

Lack of funding (32%)

Funding is not just “money for healthcare innovation.” It is money for broadband, wearable devices, clinical training, hospital maintenance, cybersecurity, and workforce capacity.

A general physician from Spain puts this bluntly on Sermo, “The lack of capital to invest would be the main cause of progress, and the others are ‘symptoms’ produced by the lack of investment.”

Regulatory hurdles (17%)

Regulatory differences create friction for multinational solutions. Deloitte’s outlook underscores the need to navigate diverse regulatory environments while modernizing healthcare industry systems and investing in digital technology platforms.

Workforce shortages (11%)

Healthcare industry staffing shortages are a massive problem. The U.S. could see a physician deficit of up to 86,000 by 2036. The issue also persists globally; the World Health Organization (WHO) projected a shortfall of 11 million health workers by 2030. Workforce shortages amplify every other barrier. Without staffing, you cannot train, implement, or safely supervise new healthcare industry tools.

How physicians can impact healthcare innovation

Sermo survey insights reveal that the majority of physicians believe they should play a larger role in shaping global health policy.

- 65% said a significantly larger role (leading health policy committees, advising governments at a national/global level, shaping funding priorities)

- 32% said in specific situations (offering clinical perspectives in policy discussions, as advisors to public health agencies, with data-driven insights)

- Just 2% said no change needed (current physician involvement in advisory boards, medical associations, and global health bodies is sufficient)

Modern innovation most often fails at the translation layer: what looks brilliant in a demo breaks down in the hospital or clinic. Physicians are uniquely positioned to prevent that failure because they understand clinical workflow, patient risk, and real-world adoption barriers. The Journal of Healthcare Leadership literature indicates that physicians increasingly tie leadership to professional identity, not just to management roles.

The practical implication is clear: physicians can shape the global health agenda by stepping into three arenas:

- Policy and standards: Advocate for interoperability, safety, and patient equity requirements that travel across borders.

- Informatics and governance: Push for high-quality data governance, bias auditing, and accountability, especially when it comes to AI in medicine.

- Resource-limited scaling: Champion healthcare industry solutions that are resilient, low-burden, and ethically deployable in settings where infrastructure is constrained.

One physician in Germany summarizes the north star clinicians keep returning to. “I think the future leaders in healthcare will be those who combine technology, data, and human-centered care, so innovators in digital health, AI diagnostics, and preventive medicine.”

How can you influence medical technology innovation?

The focus of the coming decade will shift from simply accelerating innovation to the effective and accessible deployment of new technologies. The future of global health depends less on whether we can build new tools and more on whether we can align incentives, stabilize governance, fund infrastructure, and create standards that let innovation scale without leaving patients behind.

The WHO’s role in global healthcare innovation remains essential as a convener and standard-setter, but physicians are signaling that leadership must be shared and guided by the realities of patient experience. Governments to guarantee equity, private firms to execute at speed, international organizations to coordinate standards, and physicians to keep the entire system clinically grounded and ethically accountable.

If you want a real say in what the next decade of healthcare looks like, don’t wait for a policy memo or a product launch to define it for you. Join the conversations with global physicians on Sermo, weigh in on the tradeoffs, and help vet which innovations deserve scale and which ones deserve a hard stop.

The next decade won’t be led by the loudest stakeholder. It’ll be led by physicians like you who show up early, speak clinically, and refuse to let innovation lead to inequality.