Medical errors are an unavoidable reality of modern clinical practice. They can cause patient harm, erode trust, and impose legal and operational burdens on health systems. For physicians, however, the impact is often intensely personal—an immediate shock, relentless replaying of clinical decisions, and a pervasive sense that one’s professional competence or identity has been compromised. Many physicians become “second victims“: professionals emotionally traumatized by an unanticipated patient event or mistake. That trauma is frequently minimized or ignored by institutions focused on legal exposure and systems repair, leaving clinicians to cope alone. Globally, roughly 1 in 10 patients experience harm while receiving care – more than half of which could have been preventable – underscoring the scale of potential second‑victim syndrome across healthcare settings.

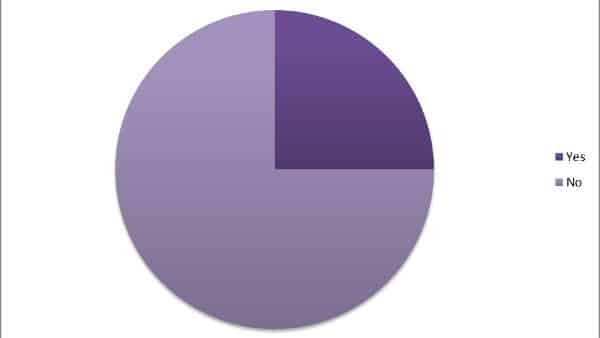

In a recent Sermo community poll, nearly 80% of physicians report having experienced moderate or significant emotional distress following a medical error or adverse patient outcome.

This article examines how often and how deeply physicians are affected, the emotions they experience, why institutional responses often fall short, and practical steps clinicians and peers can take to recover, learn, and rebuild professional resilience.

The risk of trauma after a medical error

Errors arise in complex systems where imperfect processes, time pressure, incomplete information, and human fallibility intersect. Even when the root cause is traced to systemic vulnerabilities, physicians often bear the emotional burden. The second‑victim trajectory follows a recognizable path: chaos and crisis in the immediate aftermath; intrusive reflection and replay of the event; seeking support to restore self; and, for some, eventual resolution and integration of lessons into future practice.

Physicians themselves emphasize that reflection and prevention are essential parts of recovery as one OBGYN on Sermo explains:

“It is best practice to learn from mistakes, but also to learn how to best prevent them in the first place. Critical analysis of a mistake made, even if no adverse outcome occurs, can prevent recurrence.”

Clinicians may encounter different types of medical errors, including diagnostic mistakes, medication errors, surgical complications, and communication failures. Each category carries unique risks for patients and distinct emotional consequences for physicians. One general practitioner added pragmatically, “It’s inherent to the profession. The best scribe makes a mistake. The fact is that we deal with human beings and lives, hence the doctor’s responsibility. In any case, you have to be prudent and learn from it when you make a mistake. Cheer up!”

How often does this happen in practice?

Estimates vary by setting and study design, but surveys consistently show that a significant proportion of physicians report lasting distress after adverse events, with many recalling emotional sequelae during their careers.

In one Sermo poll asking physicians how experiencing a medical error impacted their long‑term professional outlook and practice approach, 24% said positively, that it improved their practice through reflective learning; 52% said mixed, with initial distress but eventual professional growth; and 21% reported negative outcomes such as long‑lasting emotional or professional setbacks, or no significant change.

These varied responses highlight how much the surrounding environment shapes recovery. An infectious disease doctor explained that support is needed because everyone makes mistakes, adding: “Unfortunately there is a toxic environment where people think, ‘If I had to go through this, then why shouldn’t you?’ Let’s change this toxic culture!”

The professional impact can be long‑lasting. Physicians may experience hyper‑vigilance, increased ordering or referral (defensive medicine), avoidance of specific procedures or clinical scenarios, and, in some cases, decreased hours or leaving clinical practice altogether. Emotional trauma ripples outward, diminishing team capacity, eroding mentorship, and worsening patient safety if clinicians remain impaired or silent about hazards.

Dealing with a medical error: coping strategies

Recovering after a medical error requires a structured, multi‑step approach: acknowledge and validate the trauma, seek immediate peer support, use professional mental health resources when needed, and focus on systemic learning to convert harm into improvement.

Acknowledge and validate the trauma

The first step is recognition. Acknowledging the experience as trauma and normalizing emotional reactions such as shock, guilt, shame, and intrusive thoughts reduces isolation. Self‑blame is natural but rarely proportionate: errors often emerge from system vulnerabilities rather than pure individual failings. Structured reflection, rather than rumination, helps contain distress and supports recovery.

One internal medicine physician reflected, “I know that doctors at the end of the day are human and make mistakes. I think it’s important to remember that we need to forgive ourselves, and learn from our mistakes in order to not repeat them.”

A general practitioner further emphasized, “Developing emotional resilience is essential in navigating these experiences, allowing clinicians to acknowledge mistakes, learn from them, and continue providing compassionate care. A resilient mindset fosters personal growth, supports mental well‑being, and encourages a culture of transparency and improvement within medical teams. While medical errors are distressing, they can also be powerful catalysts for reflection, empathy, and system‑wide safety enhancements when approached with resilience and support.”

Seek immediate peer support

Peer‑to‑peer support is uniquely effective because it combines clinical credibility with confidentiality. Trained peer supporters provide confidential “emotional first aid,” offering validation and guiding clinicians toward practical next steps. Institutions with formal peer‑support programs report better clinician outcomes and faster return to functioning. Where programs don’t exist, safe colleagues or physician communities such as Sermo can provide confidential spaces to share, validate, and plan.

As one internal medicine doctor explained, “It is helpful to have peers and colleagues in support positions who can empathize and also help reflect on how the error was made and ways it can be avoided in the future.”

A Sermo community member and cardiologist added, “Medical errors deeply impact us. I’ve felt guilt and grief, but resilience grew through peer support, reflection, and learning. More accessible, nonjudgmental support systems are urgently needed everywhere.”

Use professional mental health resources

When distress is intense, persistent, or accompanied by insomnia, panic, or thoughts of self‑harm, a mental health professional should be involved. Counseling, trauma‑focused therapy, and physician‑specific wellness services accelerate recovery and reduce the risk of depression or burnout.

Focus on systemic learning

A forward‑looking mindset shifts from self‑punishment to system improvement. Non-punitive reviews should identify system contributors such as workflow design, staffing, cognitive overload, or poor handoffs, with corrective actions implemented. This reframing helps transform harm into durable safety improvements and restores meaning by giving the event a purpose beyond shame.

A key mechanism for transforming individual distress into collective learning is the Morbidity and Mortality (M&M) conference—a long-standing tradition across nearly every specialty. These conferences provide a structured, non-punitive forum where clinicians present cases involving complications, adverse events, or medical errors. The purpose is not blame, but shared scrutiny: to examine what happened, why it happened, and how similar events can be prevented.

What medical errors in healthcare mean for doctors

At a personal level, medical errors impose a moral ache and often a prolonged loss of confidence. At a professional level, they change behavior: more tests, more consults, slower decisions, or avoidance. Some clinicians pivot toward patient‑safety work, using their experience to prevent similar harms. Others withdraw from high‑risk practice areas or leave clinical work entirely.

As one physician on Sermo recalled, “When I started my first job as a doctor, it was very stressful to accept the fact that errors could happen. With time, I started to have a critical analysis and collaborate with experienced colleagues in order to give the best treatment to all patients and to prevent the errors that could affect patients’ outcomes.”

Acknowledging the second‑victim effect is crucial to breaking cycles of shame. Peers play a decisive role. When you recognize a colleague who has been through an adverse event, your response matters:

- Offer immediate, nonjudgmental listening.

- Provide practical support—covering clinics, helping with documentation, or arranging time off.

- Avoid and discourage moralizing, gossip, or unilateral conclusions about culpability.

- Encourage use of institutional peer‑support resources and, if needed, professional mental health care.

- Follow up over days and weeks; trauma doesn’t end at the shift’s close.

These behaviors reduce stigma, facilitate honest reporting, and promote a culture of learning rather than one defined by concealment and fear.

Physicians emotional distress when committing a medical error

The emotional landscape after an error is broad, profound, and clinically significant. Each reaction has implications for both physician well-being and patient safety.

The Sermo poll surveyed the primary feelings physicians experienced:

- 20% felt guilt and shame: Dominant early reactions that drive persistent self‑reproach and undermine confidence.

- Another 20% felt anxiety and fear of future errors: Ongoing worry that disrupts concentration, clinical judgment, and decision‑making.

- 18% felt a loss of confidence: Erosion of professional self‑trust, impairing performance and supervisory roles.

- 6% became depressed: Sustained low mood, withdrawal, and loss of motivation that reduce capacity for patient care.

- 5% experienced professional isolation: Avoidance of colleagues and teaching roles due to fear of judgment or stigma.

- 14% felt grief or sadness: Deep sorrow over patient harm and the dissonance between intention and outcome.

- 13% dealt with anger or frustration: Directed at oneself, colleagues, or systems; may catalyze advocacy or, conversely, damage relationships.

These numbers reflect both the inevitability of mistakes and the emotional toll they carry. A dermatologist reflected on the inevitability of mistakes, noting, “If you don’t make mistakes you are not human. It is best to make those mistakes early in your career, so you can think about them longer term. It also gives you the opportunity to reflect on those mistakes each time you perform the procedure so that you don’t repeat them.”

Others emphasize the enduring pain that accompanies errors. A pediatric neurologist emphasized the painful consequences, stating, “The impact of medical errors is always negative. Although you can learn from them, they always generate a feeling of guilt and pain due to their consequences.”

These emotions often manifest physically—insomnia, appetite changes, headaches, and somatic pain—and professionally through reduced concentration, slowed procedural skills, and avoidance of complex cases. Without intervention, these effects can create a dangerous cycle: impaired clinicians are more vulnerable to subsequent errors, compounding distress and jeopardizing patient safety.

How healthcare institutions fail to support doctors after medical errors

Most healthcare organizations acknowledge patient safety as a priority, but institutional support for clinicians after adverse events remains inconsistent. Frequent shortcomings include:

- Prioritizing liability over clinician well-being.

- Failure to provide immediate, confidential emotional support.

- Limited or poorly publicized peer‑support programs.

- Opaque or punitive investigations that heighten shame and fear.

- Restricted access to timely mental health care and insufficient protected time for recovery.

Poll data underscores the gap between stated priorities and lived experience. In one Sermo survey, only 15% of physicians said they were fully supported by their institution after an error. Another 25% received some support but found it inadequate, while 27% reported no support at all. Nearly a third (29%) did not seek support, reflecting both stigma and lack of accessible resources.

When asked what kind of support would have been most effective, physicians pointed to formal counseling or therapy (13%), peer support forums (15%), anonymous professional support lines (14%), institutional acknowledgement and reassurance (23%), educational resources on managing emotional responses (14%), and structured opportunities for reflection and learning (17%).

Clinicians themselves highlight the consequences of these gaps. A general practitioner stressed, “It would be important to have a notification channel for these events to receive an adequate response from the centers,” while an ophthalmologist said bluntly: “Support should be made compulsory.”

Others point to systemic failures. An emergency medicine physician observed, “It is sad to observe how the workplace does not take up its responsibilities in terms of poor work organization to the extent that these can worsen the work of physicians.” And an internal medicine doctor warned, “Mistakes cannot be avoided in the medical profession. What I am worried about is the lack of support from institutions and hospitals for health care workers who suffer psychological consequences after making mistakes.”

When institutions respond punitively or invisibly, clinicians withdraw, hide errors, and avoid reporting—actions that undermine learning and safety. A just culture where organizations hold systems accountable while treating individuals fairly reduces blame, encourages reporting, and supports recovery. Effective second-victim programs combine prompt emotional support, peer-to-peer outreach, access to counseling, clear communication about investigations, and a commitment to non-punitive learning. These measures not only help clinicians heal but also reduce medical errors by encouraging transparency and systemic improvement.

Healing the healers

Medical errors are inevitable in complex care systems, yet the emotional toll on physicians must not remain unacknowledged or unsupported. Recognizing physicians as second victims reframes the response from punitive blame and secrecy to empathy, learning, and system improvement. Clinicians recover best when they acknowledge the trauma, seek trusted peer support, engage professional mental health care when necessary, and transform the experience into systemic improvement. Institutions strengthen safety by implementing rapid, confidential peer‑support programs, conducting transparent non‑punitive investigations, and cultivating a just culture that prioritizes learning.

For physicians seeking confidential support or colleagues committed to helping, peer networks are essential. Sermo offers a private, physician‑only community where clinicians share experiences, validate feelings, exchange coping strategies, and mobilize for stronger institutional second‑victim programs. Participation in these spaces builds solidarity, empowers advocacy for humane policies, and demonstrates the compassionate responses that help both clinicians and patients heal.

Every clinician has a responsibility to care for themselves and for one another. When physicians seek help and institutions respond with compassion and structured support, the outcome is safer care, healthier clinicians, and a more resilient profession.