In a recent Sermo poll, 55% of physicians said they’d recommended a health or wellness app to a patient, while 45% hadn’t.1This near-even split highlights a profession still weighing the benefits and risks of apps within healthcare.

For some doctors, the potential of apps is undeniable. “Health applications have great potential to benefit people’s health,2” said one GP on Sermo. Others are more cautious. An ophthalmologist warned that self-diagnosis apps can “mislead patients and create unnecessary questions,2” which can complicate consultations.

With over 318,000 healthcare apps for doctors on the market in 2025,1 the conversation is shifting from whether physicians should use these tools to how the right ones can be safely integrated into working practices.

This article draws on the data from Sermo polls and comments from members to answer the questions: what risks do apps present, which ones should be used and how can physicians navigate this space?

The rise of mobile apps for healthcare professionals

Medical apps for doctors are no longer on the fringes of healthcare but instead in the pockets and workflows of most physicians. Recent data shows that 80% of doctors use smartphones3 and medical apps professionally, and nearly 90% of those integrate them into clinical practice.4 This shift signals a broader transformation in how care is delivered and managed.

But the pace of adoption has outstripped regulation. While the benefits are compelling, there’s a growing recognition among clinicians that the landscape is fraught with risk, especially in the areas of privacy, misinformation and governance. These concerns are now shaping everyday practice.

Top concerns doctors have with medical apps

Mobile applications don’t come free of scrutiny. Physicians and health professionals feel that these apps can be invasive, lack government regulation, and often misinform patients and doctors alike. Here are the main concerns doctors have with mobile health apps.

Privacy concerns

Perhaps the most pressing issue is data privacy. A recent study of 30 leading health apps found 100% had API vulnerabilities, exposing protected health information (PHI) to potential breaches, including clinical records and patient demographics.5

This matters deeply in a profession built on confidentiality. In a Sermo poll, 64% of physicians said they were aware of privacy concerns related to health apps, yet more than a third were not.1

A GP and Sermo member summed it up bluntly: “These applications collect and store a large amount of users’ personal and medical data… I believe that the field of health apps lacks strong regulation and uniform standards.2”

Others are even more wary. A physician on Sermo in Emergency Medicine said: “The use of these apps can help physicians… but the data share puts the patients in such a vulnerable position that I can’t even consider any suggestion of these apps.2”

The concern is security mixed with a lack of transparency. Patients often don’t know who has access to their data or how it’s being used, and physicians can’t easily assess that either, leaving many to err on the side of caution.

Misinformation

Beyond data security, misinformation poses another significant threat. While many apps are educational or diagnostic in nature, not all are accurate and few are regulated. One study found that 23% of clinicians feared health apps could amplify anxiety or lead to harmful self-diagnoses.6 In a Sermo poll, 43% said they had encountered a patient misled by an app.1

An Ophthalmologist on Sermo explained the consequences: “Various applications helping in self-diagnosis mislead the patient and land up in the clinic at [a] complicated stage of the disease… which is not good for the patients.2”

This delay in care is clinically dangerous. Another physician on Sermo points to the broader issue of misinformation and disinformation, warning that patients often trust apps over doctors, without understanding their limitations. Meanwhile, a physician on Sermo added: “Sometimes this information is misrepresented and instead of helping the patient it creates confusion and even harms them.2”

The challenge for clinicians is now twofold: managing patients’ conditions and unpicking the false assumptions apps may create.

Governance

Most physicians agree that health apps are outpacing the rules designed to govern them. 78% of physicians on Sermo said regulatory authorities should impose stricter controls.1

A Sermo member and psychiatrist captured the urgency: “Definitely legislation is needed, otherwise, it can be the wild wild west of healthcare.2” Moreover, another Sermo member in Emergency Medicine called for structure: “A state/federal company should be around to regulate and make sure these apps are what they say they are and that the proper studies are done to back up the claims.2”

Some progress is being made. The UK’s Criteria for Health App Assessment provides clinicians with a framework for assessing patient-facing tools. It requires evidence that the app improves outcomes, provides value for money, is easy to use and is actually used by patients.7 But this kind of guidance is still rare, and awareness is limited.

Do the benefits of healthcare apps outweigh the risks?

Despite these risks, many physicians still support the responsible use of health apps.1 The key is thoughtful, evidence-based integration into care and awareness of the pitfalls of AI, not blind adoption.

A Sermo physician in Obstetrics & Gynecology is optimistic: “Health apps are generally useful and their benefits outweigh their risks.2” While a GP on Sermo points to the physician’s role: “It’s crucial for physicians to guide their patients… and for regulatory measures to be established.2”

To protect patients and uphold care standards, physicians must stay selective, champion responsible regulation and treat apps as support tools, not clinical substitutes, until stronger oversight and evidence-based standards catch up.

Best apps for healthcare professionals right now

With physicians increasingly recognizing that well-chosen apps can improve care, enhance communication and support patient engagement,1 the next question is: which apps are worth recommending or using?

The answer depends on who the app is for and what purpose it serves. Based on Sermo insights and physician endorsements, the most effective tools fall into three key groups: those designed for patients, those built for clinicians and those that bridge the two.1

Apps for patients: Empowering self-care and healthy habits

Doctors often recommend websites and apps that help patients take ownership of their health, particularly for lifestyle change, mental wellbeing and chronic disease management.1

Apps like MyFitnessPal and Fitbit are frequently cited. A Sermo member and Internal Medicine physician shared: “I only recommend apps if I myself have used them. Fitbit for counting steps, MyFitnessPal.2” These apps support diet tracking, physical activity and goal setting – encouraging patients to stay accountable.

A GP on Sermo endorsed a broader range: “These apps offer a wide range of potential benefits… I personally measure these parameters myself using GoogleFit.2” This kind of real-life usage builds trust in digital tools.

For mental health, physicians recommend mindfulness and CBT-based apps like Headspace. A Carigologist on Sermo cited it as a key stress-reduction tool. Meanwhile, apps like Clue for menstrual tracking and Asthma Buddy for chronic conditions demonstrate the value of tailored, functional apps across life stages and disease types.

These tools offer patients information while promoting behavioral change and a sense of agency.

Apps for doctors: Enhancing accuracy, efficiency, and decision-making

When it comes to clinical practice, physicians need apps that are trusted, evidence-based and time-saving.1

For reference, many doctors prefer association-backed tools. A Cardiologist on Sermo explained: “I don’t recommend specific so-called health apps; I do recommend professional association websites such as ADA, AHA.2” This emphasis on reliability helps avoid the pitfalls of unvetted sources.

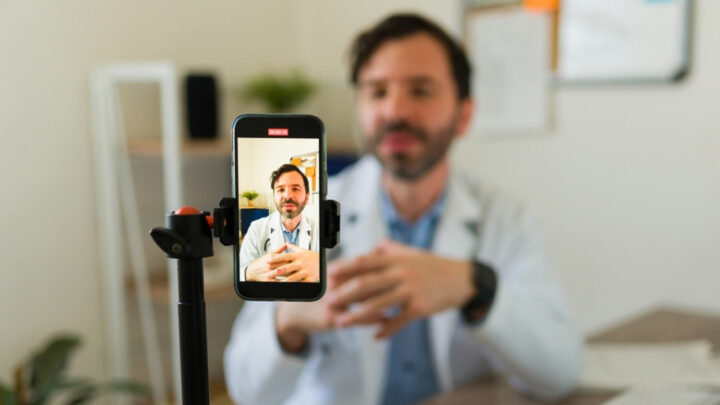

Apps that support diagnostics and clinical workflow also stand out. A Cardiologist on Sermo cited Ada, an AI-powered tool for symptom assessment, while a physician in Emergency Medicine praised how apps allow “quick access to medical advice and resources anytime and anywhere.2” These tools help speed up triage and improve decision-making.

Communication is another key area. MyChart, mentioned by several physicians, allows patients to access records and message doctors. A Dermatologist on Sermo noted its potential in developing countries: “It’s good to have all patient records in digital version.2”

Beyond clinical tools, many physicians also value platforms that foster professional connection and shared learning. Sermo is a trusted space for doctors to network globally, exchange insights, and collaborate on complex cases with peers worldwide. With 1+ million verified members, it’s both an app for physicians and a global medical community.

Your takeaway

Healthcare apps are here to stay, but thoughtful integration is key. From lifestyle trackers to clinical support tools, the best apps are those that are evidence-based, secure and matched to clear goals. Physicians favor apps that are clinically relevant, trusted and purpose-driven, especially those they’ve personally tested.

As new UK regulation shows, and with the rise in medical ai platforms, clinicians play a vital role in guiding their use: helping patients avoid misinformation, protecting privacy and recommending tools that genuinely support care.

As adoption grows, informed clinical judgment remains the most important safeguard in the digital health era.

Join the conversation on Sermo

Sermo is where real physicians come together to navigate the evolving world of healthcare apps, from sharing trusted tools to debating the risks.

Whether you’re joining in on polls, contributing to case studies, or taking part in discussions on the latest medical breakthroughs, Sermo is a lively community of physicians shaping the future of healthcare.

Footnotes

- Sermo, 2024. Poll of the Week: The Health App Conundrum: Beneficial or Detrimental for Patients? [Poll]. Sermo Community.

- Sermo member, 2024. Comment on Poll of the Week: The Health App Conundrum: Beneficial or Detrimental for Patients? [Poll]. Sermo Community [Private online forum].

- Healthcare IT News, 2011. Smartphones, medical apps used by 80 percent of docs.

- Mobasheri MH, King D, Johnston M, et al The ownership and clinical use of smartphones by doctors and nurses in the UK: a multicentre survey studyBMJ Innovations 2015;1:174-181.

- Compliancy Group, 2024. Healthcare App Security: Are Health Apps Putting PHI at Risk?

- Giebel GD, Abels C, Plescher F, Speckemeier C, Schrader NF, Börchers K, Wasem J, Neusser S, Blase N. Problems and Barriers Related to the Use of mHealth Apps From the Perspective of Patients: Focus Group and Interview Study. J Med Internet Res 2024;26:e49982. doi: 10.2196/49982. PMID: 38652508. PMCID: 11077409.

- Public Health England, 2017. Criteria for health app assessment.