Clinicians have widely debated the role of empathy in medicine and its clinical applications. As the literature supporting empathy’s clinical efficacy expands, there are shifts in long-standing patient care standards, and as one physician on Sermo says, “It can be difficult to show your human side as a doctor since we are usually trained to maintain a level of professionalism at all times. However, it is important to be human and to show emotion because it helps patients feel more comfortable and supported.”

Medical school faculty now emphasize empathy’s role in evidence-based care, as reflected by Sermo’s members who cite “physician empathy” as a key component of doctor-patient relationships.

One physician wrote that “working on developing empathy towards patients can improve the doctor-patient relationship and understanding of their emotional needs.”

Below is a guide to the existing consensus on empathy in medicine. Learn why empathy is important in medicine and its implications for patients and clinicians.

Empathy in medicine: What does it mean?

Think of clinical empathy as a physician’s ability to understand the basis of patients’ feelings—and communicate that understanding with patients. “By showing empathy and understanding, healthcare providers can instill hope and foster a healing environment,” notes one doctor on Sermo.

Traditionally, Western medicine emphasized detached concern to ensure objectivity in patient care. While detached concern influenced the development of modern care standards, groups of researchers suggest that it prioritizes disease eradication over patient-centered care—an ideology that focuses on treating the condition rather than the person.

A growing body of research supports the importance of empathy in medicine, showing that empathetic care leads to better outcomes. It also suggests detached concern’s limitations. Recognizing this, 94% of Sermo’s community of physicians agree that patients respond better to empathetic care, while 47% believe traditional medical training restricts physicians’ capacity to develop emotional connections.

Importance of empathy in healthcare

About six out of 10 (59%) of Sermo’s physician community cite empathy as the most important component in developing effective communication skills. Here are some of the impacts empathic doctors can have:

Increased diagnostic accuracy

Patients who view their provider as high in empathy and compassion in medicine report 80% fewer errors. Similarly, empathy’s influence on diagnostic accuracy may extend to indirect patient contact. Examining 2,300 hospitalized patients, researchers indicated that charts containing stigmatizing labels—like describing a patient as “difficult”—predicted diagnostic error. After adjusting for confounders, diagnostic errors occurred in 8.2% of cases with negative language compared with 4.1% of those without.

Improved patient satisfaction

Empathy plays a huge role in the patient experience. One Sermo physician explains, “We can truly make a positive impact on the lives of those we serve through compassion. A physician’s compassionate bedside manner can provide solace and comfort to a patient with a life-altering diagnosis.”

Researchers analyzed 14 randomized controlled trials in diverse medical settings to determine whether a physician’s empathy improves patient satisfaction. And 100% of these trials associate higher patient satisfaction with empathy-focused interventions, though improvements varied across study designs. Furthermore, orthopedic researchers identified physician empathy as the strongest predictor of patient satisfaction.

Oncological researchers note similar patient outcomes. Sermo’s community of oncologists indicates that fear (43%), depression (30%) and anxiety (27%) are the three emotions that patients most prevalently express. One group of researchers reported that oncology patients who perceived clinical empathy exhibited lowered emotional distress and greater satisfaction. Notably, oncologists’ self-rated empathy did not predict these outcomes.

Reduced medical errors

In addition to increased diagnostic accuracy, one cross-sectional study of 309 hospital nurses found that higher compassion scores predicted fewer medical errors.

Counter-traditionally, empathy also may reduce physician burnout—which influences clinical efficacy by extension. One national U.S. study found that physicians with burnout are over twice as likely to self-report major medical errors compared with those without burnout.

Augmented clinical outcomes

Clinical empathy may positively influence both somatic and psychiatric patient outcomes.

Researchers followed approximately 600 type 2 diabetes patients for 10 years. Patients who reported higher primary care clinician empathy at year one experienced a lower risk of all-cause mortality. A larger study of approximately 21,000 diabetic patients found that those who received care from highly empathic primary care physicians experienced lower rates of acute metabolic complications.

Psychiatrically, a meta-analysis of 82 studies indicated that a psychotherapist’s empathy is a moderately strong predictor of improved patient outcomes. Across diverse treatment modalities and patient populations, higher therapist empathy correlated with greater reductions in psychological distress and symptom severity.

Why some doctors lack or are unable to show empathy in medicine

Lack of capacity and teachability are two primary debated barriers to empathic care.

Clinical detachment models stem, in part, from the idea that physicians can’t empathize with every patient due to the inherent emotional strain and the medical system’s time limitations. Reflecting on this, one GP posted on Sermo, “Medical care in a public hospital is limited by the number of appointments scheduled, lasting 15 minutes each, very little time for quality care and implementing the recommended guidelines for each patient.”

Moreover, 70% of Sermo’s physician community express concerns about the impact of suppressing vulnerability in patient interactions. Additionally, some argue that physicians do not receive sufficient training in empathetic care. Others maintain that educators cannot teach empathy. An Italian cardiologist wrote on Sermo about physicians’ capacity to deliver bad news empathetically, “Frankly I do not know if you can teach something that depends largely on your personal predisposition to empathy and the path that each of us performs in their professional growth. I learned on my skin to handle difficult communication, probably at the cost of various errors and adjustments over time.”

Adding to the conversation, an orthopedic surgeon noted, “I believe that currently the faculties prepare more or less well for the doctor to be able to have a general knowledge of medicine, but nobody is prepared to act in difficult emotional situations.” Medical training institutions are increasingly responding and adopting curricula on empathic care.

4 practical strategies for expressing empathy with patients

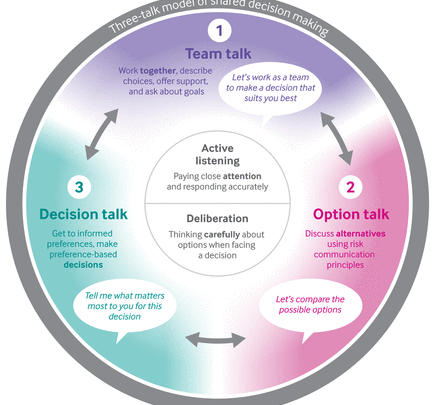

The Canadian Medical Association (CMA) proposed a four-step framework for providing empathic communication:

- Recognize and label emotions: Assess the patient’s emotional state in the moment and classify their specific feelings, like anger, sadness or worry.

- Investigate and understand: Explore the underlying reason(s) for the patient’s emotions. Ask open-ended questions and encourage them to articulate their motivations. Avoid judgment and remain aware that your position can influence the conversation.

- Facilitate emotional progress: To support the patient’s emotional state, help them identify effective strategies they have used and benefited from in the past. Or, share approaches you have personally found helpful in similar circumstances.

- Monitor nonverbal communication: One Sermo member and physician says, “Nonverbal cues, such as patting the shoulder or shaking the patient’s hand, can communicate compassion and understanding in ways that words cannot by reflecting empathy for our patients.” Other non-verbal cues include maintaining eye contact, nodding and leaning forward to convey attentiveness.

SPIKES, NURSE and the Calgary-Cambridge model are three other complementary and evolving models. SPIKES—setting, perception, invitation/information, knowledge, empathy and summarize/strategize—is an evidence-based six-step framework for delivering bad news.

Complementarily, NURSE—name, understand, respect, strength, support and explore—is a mnemonic for five types of empathic responses that clinicians can adopt to empathically address a patient’s emotions.

The Calgary–Cambridge model provides a framework for structuring medical interviews. In contrast to SPIKES or NURSE, which apply to specific scenarios, the Calgary–Cambridge model covers the entire consultation process. It offers a practical, integrated method for teaching both empathetic communication and effective information gathering.

Join 1+ million other physicians on Sermo

Sermo polled its global community of physicians, asking, “How can physicians rebuild empathy in medicine?” Over 40% cited reduced workloads, while 16% cited peer support. Another 36% cited training in compassionate care and medical education reform.

Speaking on their education in empathic care, one family medicine doctor posted, “See one, do one, teach one. I learned in medical school by watching my mentors deliver bad news, and emulating the good ones while learning how not to deliver bad news from the ones that couldn’t connect.”